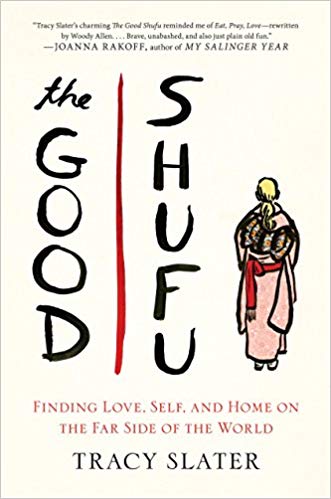

Women’s increasing equality in the U.S., along with a changing economy, has continued to expand women’s prevalence in the workplace at all stages of life—making our dilemmas about balancing work roles with those of traditional marriage and motherhood unlikely to go away anytime soon. How, for example, can I even find the time to date with increased work responsibilities? How can I negotiate in a relationship in which I may be better equipped (or expected) to both work and take care of the household? Can I have a successful career and a happy marriage? These concerns make the premise of Tracy Slater’s new memoir, The Good Shufu: Finding Love, Self, and Home on the Far Side of the World, particularly intriguing.

A feminist and a Ph.D. from a privileged American background, Slater asked herself similar questions. She decided on independence and a self-made career as a freelance writer and educator in lieu of a potentially restrictive marriage, yet she ultimately traded these staunch principles for love and a decidedly traditional marriage. What earth-shattering romance prompted her to embrace such a radically different experience? While spending a semester in Japan, teaching English in an MBA program, Slater fell in love with Toru, a Japanese businessman with whom she couldn’t really communicate, especially on the meaningful level she desired. They continued their relationship, most of it long-distance, and eventually married after much deliberation and experimentation, mostly on her part, about whether their relationship would be sustainable.

Shufu is the Japanese term for, as Slater puts it, “housewives who after marriage give up their careers,” and Slater leads us to understand that in Japanese culture, the majority of female workers choose this life. Even though Slater prefaces each chapter of her account with quotations from books about culture shock, most of The Good Shufu dwells on cultural differences that may have little affected her had they not been exacerbated by her own insecurities, her carelessness in preparation for spending a considerable amount of time in a foreign country and culture, and her reluctance to embrace a non-Western perspective. Slater honestly admits she accepted her teaching job in Japan on a lark (mostly because of the money and her love for travel), read just a few guidebooks and made no real attempt to learn Japanese (which I thought was pretty crazy). But this “strategy” also informed the rest of her approach to the culture once she decided to commit to Toru in a long-term relationship. Two years in, she still hadn’t begun to bridge their communication gap by learning the language! Slater held the “hazy belief that remaining impervious to Japanese would shield me from becoming too immersed in a culture and world I still approached with ambivalence.”

The marriage in which she is a good shufu comes very late in the book, and the challenges seem not much different from a traditional American relationship’s give-and-take: Compromises about where to live, when and if to have children, how to care for aging in-laws, as well as housekeeping and fertility issues, all seem rather run-of-the-mill and not unduly influenced by Japanese society. I did love peeking in on her experiences and getting a bird’s eye view of Japanese food and culture. Slater is an astute observer, skilled at conveying cultural differences; these are valuable and interesting, but they were tempered by the tedium with which I viewed her reactions. The way she compares everything she encounters in Japan to the customs of her own upbringing in her beloved hometown of Boston—to the detriment of her beloved Toru—distracted from the experience overall.

Featured Photo courtesy of Anatole Papafilippou